Main Content

Sal Mangiafico and Amy Rowe, Rutgers Cooperative Extension

There have been some topics in the news lately related to tickborne diseases. One is the apparent rise in alpha-gal syndrome cases in some parts of New Jersey. Another is the potential for a Lyme disease vaccine for humans.

This article will briefly address these topics, along with a quick overview of tickborne diseases, where to get ticks identified and tested, and how climate change may affect ticks in our environment.

Ticks in New Jersey

New Jersey is home to several ticks that bite humans.

- Commonly found ones include the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), blacklegged tick (or, deer tick, Ixodes scapularis), and lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum).

- An invasive tick that is common in some areas is the Asian longhorned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis).

- And a new tick to New Jersey, that is a disease vector, is the Gulf Coast tick (Amblyomma maculatum).

There are other ticks in New Jersey that may bite other animals but are of less concern because they do not usually bite humans.

For images of common tick species in New Jersey and more information, see ticks.rutgers.edu/ticks.

Tickborne diseases

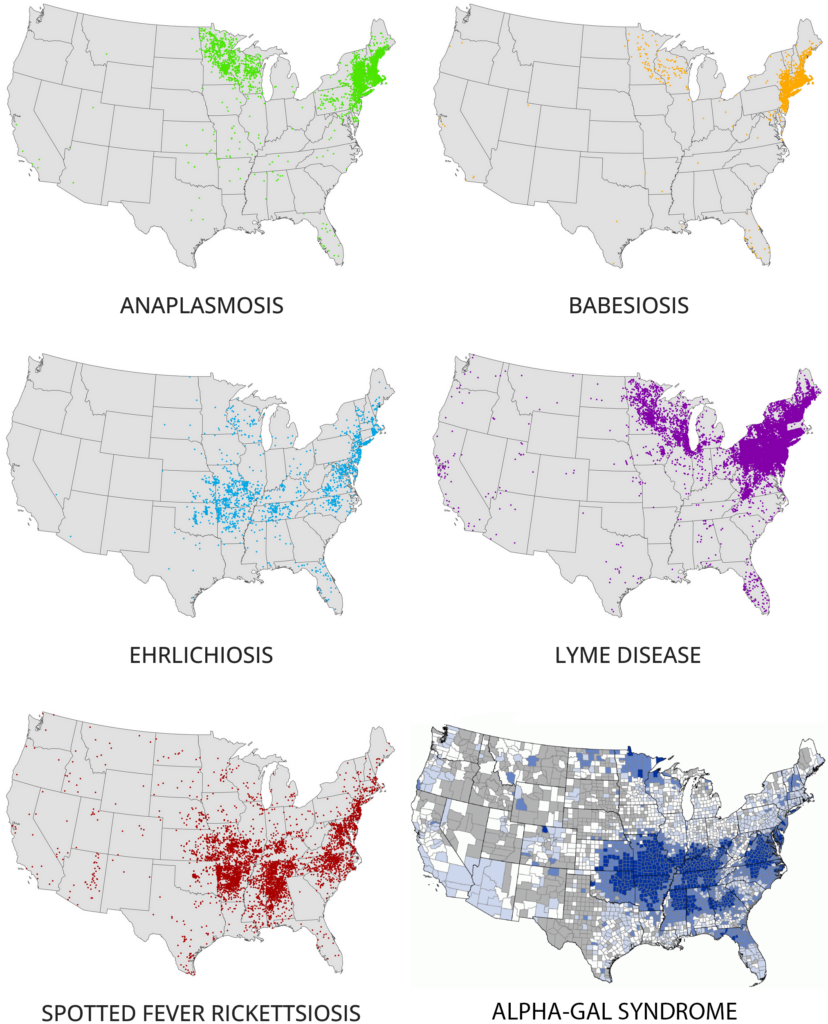

Ticks in New Jersey can carry diseases to humans and other animals. The infectious agent in these diseases may be bacteria, viruses, or protozoans. Certain diseases are often carried by a specific species of tick.

For example,

- Lyme disease is associated with blacklegged ticks, and these ticks also carry anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and the Powassan virus.

- Lone star ticks carry Ehrlichia and are also implicated in causing alpha-gal syndrome.

- Spotted fever rickettsiosis, including the well-known Rocky Mountain spotted fever, is carried by American dog ticks and Gulf coast ticks.

In general, immediate symptoms of some of these diseases may not be very noticeable. There may be a rash around the bite site, or there may be flu-like symptoms following the bite. Often, immediate symptoms may be lacking. However, the effects of some of these diseases can be long-term and debilitating.

Ticks do not transmit disease immediately upon biting. Disease transmission may take up to 24 hours or may be faster for some diseases and ticks. And time of transmission may vary based on if the tick has fed recently or not.

In all cases, it is prudent to perform tick checks after being outdoors to find any crawling or attached ticks. And to remove ticks promptly.

More comprehensive discussions about tickborne diseases can be found at CDC (2022a), www.cdc.gov/ticks/tickbornediseases/index.html.

Alpha-gal syndrome

Anecdotally, cases of alpha-gal syndrome, or diagnoses of the condition, are increasing in some parts of New Jersey with lone star ticks becoming more prevalent.

Alpha-gal syndrome causes an allergic reaction to a carbohydrate found in mammal meat (red meat) and dairy products, or in other animal-based products like gelatin in medicine capsules.

Reactions to eating the alpha-gal carbohydrate vary. Milder symptoms include hives, faintness, or diarrhea. But severe symptoms include anaphylaxis and can be life-threatening. Symptoms usually occur 2–6 hours after ingesting alpha-gal. But people with alpha-gal syndrome may not experience symptoms every time they eat meat or dairy.

For more information on alpha-gal syndrome, see CDC (2023), www.cdc.gov/ticks/alpha-gal/index.html.

Effects of climate change on tick abundance

Ticks may thrive in warmer weather, wetter weather, and where the climate promotes dense vegetation. As climate affects temperature, rainfall patterns, and the composition of plant communities, tick populations may be affected.

- Tick species from outside New Jersey may move into our state. One example of this is the Gulf Coast tick, which traditionally has been found south of New Jersey, now has established populations in our state. (More information can be found at ticks.rutgers.edu/ticks/3).

- Milder winters may mean that ticks will be more active earlier in the spring, later into the fall, and in warm spells during the winter.

- Some species of tick may become more abundant as the environment changes. One example of this is the lone star tick. Anecdotally, its abundance has increased in some parts of the state in recent years.

A vaccine for Lyme disease?

Dogs in the U.S. are eligible to receive a vaccine for Lyme disease. A Lyme disease vaccine for humans, LYMERix, had been developed and marketed in the 1990’s, but was discontinued in 2002, due to a lack of consumer demand, perhaps partially fueled by anti-vaccination sentiment.

Currently, a Lyme disease vaccine, developed by Valneva and Pfizer, is in Phase 3 human trials. The vaccine seeks to address the North American and European strains of the Lyme disease bacterium, Borrelia.

Information on tick habitat, avoiding ticks, and preventing tick diseases

Information about New Jersey’s ticks’ life cycles, tick removal, differences between a variety of tick species, and how to reduce tick habitat around your home can be found in the Rutgers Earth Day Every Day webinar from 2020 with Amy Rowe.

For a short newsletter article on Lyme disease, tick protection, and tick removal, visit Tick Tock, Tick Tock… Countdown to Summer Tick Safety by Steve Yergeau.

Ocean County Cooperative Extension provides a short factsheet on identifying and preventing tick diseases.

Getting tick specimens identified and tested

The Rutgers Center for Vector Biology offers free identification of tick specimens by photo, and testing of physical tick specimens for diseases. At the time of writing, tick species tested for diseases are the blacklegged tick, lone star tick, and Gulf Coast tick.

For more information about the process, and to see specifically which tick diseases are tested for, see the Center for Vector Biology’s NJ Ticks for Science or a summary of the program and promotional materials.

Be sure to continue checking for ticks late into the fall, as it is mating season and ticks are on the move. Females require a bloodmeal to gain the required proteins to produce and lay eggs, so they are very active during this time of the year.

References

[CDC] U.S. Centers for Disease Control. 2022a. Tickborne Diseases of the United States. www.cdc.gov/ticks/tickbornediseases/index.html

[CDC] U.S. Centers for Disease Control. 2022b. Overview of Tickborne Diseases.

www.cdc.gov/ticks/tickbornediseases/overview.html

[CDC] U.S. Centers for Disease Control. 2022c. Lyme disease vaccine. www.cdc.gov/lyme/prev/vaccine.html

[CDC] U.S. Centers for Disease Control. 2023. Alpha-gal Syndrome. www.cdc.gov/ticks/alpha-gal/index.html

Mangiafico, S.S. 2023. Rutgers Tick Identification and Disease Testing. Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Cumberland County. cumberland.njaes.rutgers.edu/2023/08/02/rutgers-tick-identification-and-disease-testing/

[NJAES–CVB] New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station Center for Vector Biology. 2023. NJ Ticks 4 Science! ticks.rutgers.edu/

Ocean County Cooperative Extension. 2022. Tick Safety Information from Rutgers University, New Jersey Department of Health and the CDC. ocean.njaes.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Tick-one-pager-061422-ACC.pdf

Powell, A. 2023. So why does my dog get Lyme disease vaccine, and I don’t? Harvard Gazette. news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2023/07/the-case-of-the-missing-lyme-vaccine/

Rowe, A. 2020. Ticks and Lyme Disease (webinar recording). Rutgers Earth Day Every Day. www.youtube.com/watch?v=BAlh5DPk1rE&list=PLKx8NLAujm_lpOimXWyHxPD613H7HjZKd&index=20

Thompson, J.M., Carpenter, A., Kersh, G.J., Wachs, T., Commins, S.P., Salzer, J.S. 2023. Geographic Distribution of Suspected Alpha-gal Syndrome Cases — United States, January 2017–December 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023; 72:815–820. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7230a2.htm

Yergeau, S. 2022. Tick Tock, Tick Tock… Countdown to Summer Tick Safety. Rutgers Cooperative Extension. salem.njaes.rutgers.edu/2022/06/01/tick-tock-tick-tock-countdown-to-summer-tick-safety/