Main Content

by Paige Radcliffe, Douglas Zemeckis, and Steve Yergeau

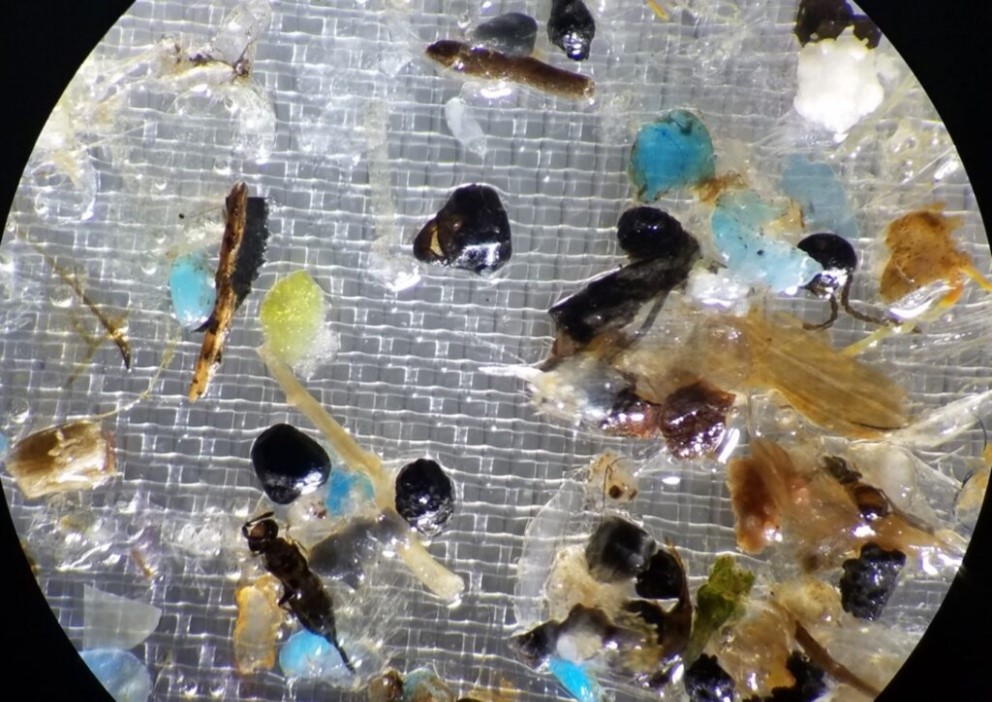

A hot topic and important environmental issue is the increasing prevalence of microplastics in our marine environments. Microplastics, which are defined as plastic particles smaller than 5 millimeters in size (Figure 1), are often broken down from larger plastic debris that find their way into our marine environments. There are many pathways by which plastic pollution occurs and numerous downstream environmental effects.

This article describes the origin of microplastic in the environment, what individuals can do to reduce plastic pollution in marine environments, and recommendations on what individuals can do to reduce plastic pollution that often ends up in our marine ecosystems. Following these recommended practices will make for more responsible environmental stewards of our natural resources and aid in the protection of New Jersey’s habitats throughout the state.

How do plastics enter our oceans in the first place?

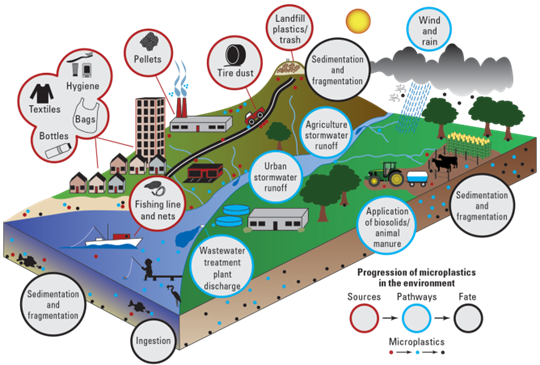

Plastics can enter waterways, streams, and rivers that ultimately lead to the ocean (Figure 2). There are many ways by which plastics can become pollution including littered items on streets, trash blown from dumpsters, washing and drying clothing, tire dust, agricultural runoff, and overflow during rain events (Figure 3). The concentration of plastics in storm drains can be dense but as it spreads to our waterways in trace amounts it makes the issue harder to get a grasp on. Once plastics enter brackish or saltwater ecosystems they are weathered down by environmental conditions. Ultraviolet radiation from sunlight and wave action fragment plastic into smaller pieces until they are eventually microplastic particles (Tibbetts, 2014).

Figure 1: Microplastics as seen under a microscope. (Image credit: marine.rutgers.edu, 2024.)

Figure 2: Progression of microplastics in the environment. (Image credit: usgs.gov, 2023.)

Figure 3: One of the many ways that plastics can enter the marine environment. (Image credit: NOAA, 2016.)

What happens when microplastics enter the marine environment?

Research has noted that microplastics are eaten by plankton, one of the smallest marine invertebrates, therefore making bioaccumulation through the food web a common occurrence. Some larval fish species are drawn to eating microplastics due to their color, size, and odor. Microplastics can also be a vector for bacteria growth. Different types of microplastics can have varying impacts. For example, Styrofoam has the tendency to acquire biofilm — microorganisms that grow on the Styrofoam surface — making it a source for trash blooms. Plastics never fully degrade, and ingestion by marine mammals and larger species can result in mortality. Lingering and drifting plastic can smother marine environments and cause havoc on habitats such as reefs and seagrass meadows (NOAA, 2016).

Fortunately, many species have proved adaptable to microplastics in the marine environment by being able to eliminate these particles completely through egestion — that is, excreting the plastics undigested. Bivalves, such as oysters and clams, which are filter feeders and eat phytoplankton, have also demonstrated the ability to reject microplastics through their pseudofeces without actually ingesting them (Ward et al., 2019).

What can you do to make a personal impact?

The best way to prevent microplastics is to keep plastics from entering the ocean in the first place. Microplastics stem from larger plastics and marine debris, so tackling the issue from the root is the best course of action, for example, looking to your county, municipalities, and other local partners for opportunities to recycle. Being conscious of recycling in your community plays a large impact on what items can actually be repurposed based on recycling codes and special waste separation and drop off options. Also, awareness of collection sites at docks and marinas for fishing line, old nets, and trap materials will prevent these excess materials from being lost at sea. Participating in seasonal beach clean ups is an important effort, as is being mindful of other methods of citizen science and outreach projects.

The advancement of microplastic filter technology such as the “artificial root” filter, which is designed to sequester microplastics from outflowing streams before reaching the ocean, is a newer innovation (See Additional Resources below). Dryer filters and laundry ball devices are also crucial in preventing microfibers from synthetic fabrics, which are considered a form of microplastic, from entering the environment. These can work on dryer exhaust or the washer wastewater stream. Microfibers have been documented in almost all of earth’s ecosystems, including our drinking water and food. Upcycling or donating clothing, instead of it ending up in landfills, is another crucial effort because microfibers and polyester are prominent marine debris. Initiatives taken by the state of New Jersey to prevent microplastics in the marine environment include a ban on plastic bags (implemented in 2022) and the federal Microbead Free Waters Act (See Additional Resources below).

Stay mindful, be informed, and do your part!

In summary, recommended practices for reducing plastics pollution in the ocean include:

- Prevent plastic from having the ability to enter the ocean in the first place through recycling, upcycling, and cutting down on purchasing single use items

- Be aware of local recycling regulations, special waste separation requirements, and clothing donations

- Use new technologies to sequester microplastics such as laundry ball and dryer filter devices

The following are additional resources where you can learn more about microplastics pollution:

Additional Resources

Citizen Science – Microplastic Sampling September 14–29th

Microplastics — The Plastic Wave Project

Clean Ocean Action – Fall Beach Sweep October 19th

Clean Ocean Action: Beach Sweeps

Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Ocean County

Rutgers Cooperative Extension of Ocean County

Microplastics: Tiny Particles with Major Impacts (webinar with Judith Weis)

Microplastics: Tiny Particles with Major Impacts

Ocean County Department of Solid Waste Management

Solid Waste Management | Ocean County Government

Ocean County Recycling Guide

u-1-4734-2023-OC-Recycling-Guide.pdf (lakewoodnj.gov)

Ocean County Recycling Guide for Vacationers

cd4805d1-a874-4b55-9a13-d246bd000978.pdf (ocean.nj.us)

Ocean County Recycling Guide for Boat Owners

a194229d-85e5-41e3-8d8b-75c0a8401cb8.pdf (ocean.nj.us)

New Jersey’s Statewide Initiatives

Single-Use Plastic Bag and Polystyrene Foam Food Service Ban- May 2022

NJDEP| New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection | Get Past Plastic

Federal Microbead-Free Waters Act – FAQ

The Microbead-Free Waters Act: FAQs | FDA

Laundry Ball & Filter models to prevent Microfibers

Cora Ball – The Laundry Ball Protecting the Ocean and Your Clothes

PlanetCare

PlanetCare | The Most Effective Solution To Stop Microfiber Pollution

“Artificial Root” Microplastic Filter Trap

Our Tech, The Plastic Hunter — PolyGone, Systematic Solutions for Microplastic Pollution (polygonesystems.com)

References and Figure Sources

Figure 1: Microplastics as seen from a microscope, (marine.rutgers.edu)

Microplastics – Rutgers University Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences

Figure 2: Microplastics sources, pathways, and fate conceptual diagram, (USGS)

www.usgs.gov/programs/environmental-health-program/science/usgs-science-opportunities-related-nationally#overview

Figure 3: Plastics in the ocean: how they get there, their impacts, and our solutions (NOAA)

blog.marinedebris.noaa.gov/plastics-ocean-how-they-get-there-their-impacts-and-our-solutions

NOAA. (2016). Marine Debris Program. Plastics in the Ocean.

Plastics in the Ocean: How They Get There, Their Impacts, and Our Solutions | OR&R’s Marine Debris Program (noaa.gov)

J. Evan Ward, Shiye Zhao, Bridget A. Holohan, Kayla M. Mladinich, Tyler W. Griffin, Jennifer Wozniak, and Sandra E. Shumway. (2019). Environmental Science & Technology, 53 (15), 8776-8784 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.9b02073

Selective Ingestion and Egestion of Plastic Particles by the Blue Mussel (Mytilus edulis) and Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica): Implications for Using Bivalves as Bioindicators of Microplastic Pollution

Tibbetts, John H. (2014). South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium.

www.scseagrant.org/how-microplastics-are-shredding-ocean-health/#:~:text=On%20the%20sea%20surface%2C%20ultraviolet,food%20particles%20for%20tiny%20organisms